Author: Vikranth Srivatsa, Dongming Li, Yiying Zhang, Reyna Abhyankar

TL;DR:

Today’s LLM serving systems like vLLM and TGI primarily use a scheduling approach called iterative scheduling (or continuous batching), which decides the batch composition at every round (or every few rounds) of model forwarding. Different from prior serving systems that schedule the next batch after the entire current batch finishes, iterative scheduling promises to improve GPU utilization and LLM serving rate, but with a key assumption: the scheduling overhead can be ignored. While this assumption generally held in the past, it is worth reexamination as today’s LLM inference kernels run much faster than before and as more scheduling tasks and considerations get added.

To understand the tradeoffs of iterative scheduling in today’s environment, we performed a detailed analysis of two popular SoTA LLM inference systems, vLLM and SGLang. Our evaluation results show that vLLM’s scheduling overhead can take more than half of the total inference time. By breaking down its scheduling functionalities, we found the major overhead came from tensor pre- and post-processing. Our evaluation of SGLang shows much lower scheduling overhead, primarily due to its simplified tensor processing. Based on our evaluation results and source code analysis, we make suggestions on potential improvements in vLLM’s scheduler.

Background and Motivation

LLM inference today performs batched model forwarding by sending a batch of requests to the GPU at a time. Prior LLM inference systems schedule a subsequent batch after all the requests in the current batch finish their generation, which causes GPU resource waste as some requests in a batch finish earlier and wait for the others. Iterative LLM inference scheduling mitigates this issue by constructing a batch after each model forwarding iteration, where each iteration executes a prompt prefilling and/or one decoding token generation. With chances of adding new requests to a batch at any iteration, iterative scheduling largely improves GPU utilization.

Typically, LLM scheduling involves post-processing requests (detokenization) from the previous batch, selecting requests to include in the next batch, and preparing a new request for model forwarding. Note that pre- and post-processing can be treated as tasks independent of an actual scheduling algorithm; we include them in the “scheduling overhead” in this work, as they are always and only called when the scheduler is invoked.

A key assumption iterative scheduling makes is that the scheduling delay (including other tasks invoked together with the scheduler) is much smaller than an iteration of model forwarding time. Thus, scheduling at each iteration is acceptable. Two new developments in LLM inferencing are challenging this assumption. First, model forwarding has become much faster with new inference kernels like FlashInfer3. As a result, the relative time spent on scheduling is more significant. Second, today’s scheduling systems often undertake more tasks with more considerations. For example, a technique called chunked prefill separates a prompt into multiple chunks, each executed in one iteration with other decoding requests, thereby improving GPU utilization. Supporting chunked prefill adds to the tasks of a scheduler at the iteration level. Such added tasks inevitably increase the scheduling delay.

Has the tipping point come that scheduling now dominates the model inference time?

To answer this question scientifically, we performed a detailed study on two LLM inference systems, vLLM and SGLang.

Figure 1: Illustration of Iterative Scheduling. Rx represents xth request. Ix represents xth iteration. In I3, I4, I5, I6, new requests get added to the batch as previous requests finish.

Evaluation Methodology

We ran vLLM v0.5.4 and the latest SGLang (commit hash tag 3694f8f996e25c862cd67057e2bfa5844900fc98). We set up vLLM v0.5.4 with its default configurations, which use the FlashInfer3 kernel, adopt chunked prefill, disable prefix caching, and disable multi-step scheduling. We set the token bucket size (maximum number of tokens in a batch for each iteration) to 512 to ensure the model forwarding is compute-bound. We use the default SGLang configurations, which use the same FlashInfer3 kernel, enable prefix caching, has no chunked prefill, and enable 10-step scheduling when a batch has no prefill (i.e., schedule after 10 iterations if a current batch is decode-only). We conducted our profiling using the Nvidia Nsight System, with time measurement code injected to capture precise model forwarding and scheduling times.

Our test workloads included synthetic and real workloads. Real datasets include ShareGPT, which represents chat usages and has similar output and prompt lengths, and LooGLE, a document QA dataset with an average prompt-to-output length ratio of 32,000 to 50. For synthetic workloads, we fix the prompt and output length, for example, to 1024-token prompt and max 64-token output (“1024:64” in the figures below) with fake tokens. By default, we send 300 requests at once to the system to create a constant load unaffected by request arrival patterns. Doing so ensures that our measurement of model forwarding and scheduling time, the focus of this study, is unaffected by request arrival patterns.

We benchmarked three models — the Llama-1.3B model, the Llama3-8B model, and the Llama3-70B model — to assess the performance variations across different model sizes. We ran our experiments on one Nvidia A6000 GPUs in our local Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 5218 servers and up to four Nvidia A100 GPUs in RunPod.

vLLM Scheduling Overhead Analysis

Figure 2: vLLM Scheduling Time vs. Model Forwarding Time on A100 GPUs on LLama 1.3b

Figure 3: vLLM Scheduling Time vs. Model Forwarding Time on A100 GPUs on LLama 8b

Figure 4: vLLM Scheduling Time vs. Model Forwarding Time on A100 GPUs on LLama 70b

Figures 2-4 presents the median per-iteration model forwarding time and scheduling time of vLLM running different workloads and models. Our results show that scheduling can take as high as half of the total end-to-end inference latency. The scheduling overhead gets relatively higher with the smaller model because the model forwarding time of a small model is faster but the scheduling overhead is not impacted by model sizes as much. Comparing across workloads, we observe workloads with longer output generation (1024:1024, ShareGPT) incur higher scheduling overhead. As we will show in the next section, vLLM’s scheduling overhead increases with more requests in a batch. Workloads with longer outputs have more requests performing decoding stages. For the same batch size in token counts, a batch can accommodate more decoding requests than prefill requests. Thus, for workloads with more decoding, the number of requests in a batch is larger, causing higher scheduling overhead. Loogle has the lowest scheduling overhead for two reasons. First, its model forwarding time is longer than other workloads. Second, the number of requests in a batch is smaller than other workloads, causing less scheduling overhead.

Figure 5: vLLM Scheduling Time vs. Model Forwarding Time on A6000 GPUs on Llama 8b

Figure 6: vLLM Scheduling Time vs. Model Forwarding Time on A6000 GPUs on Llama 1.3b

We also tested the same set of workloads on our local servers, each consisting of two A6000 Nvidia GPUs and Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 5218 CPUs. Figures 5-6 presents these results. The A6000 GPUs model forwarding is much slower than A100. The relative scheduling overhead is lower than A100, as the model forwarding running on GPU gets slower.

vLLM Scheduling Overhead Breakdown

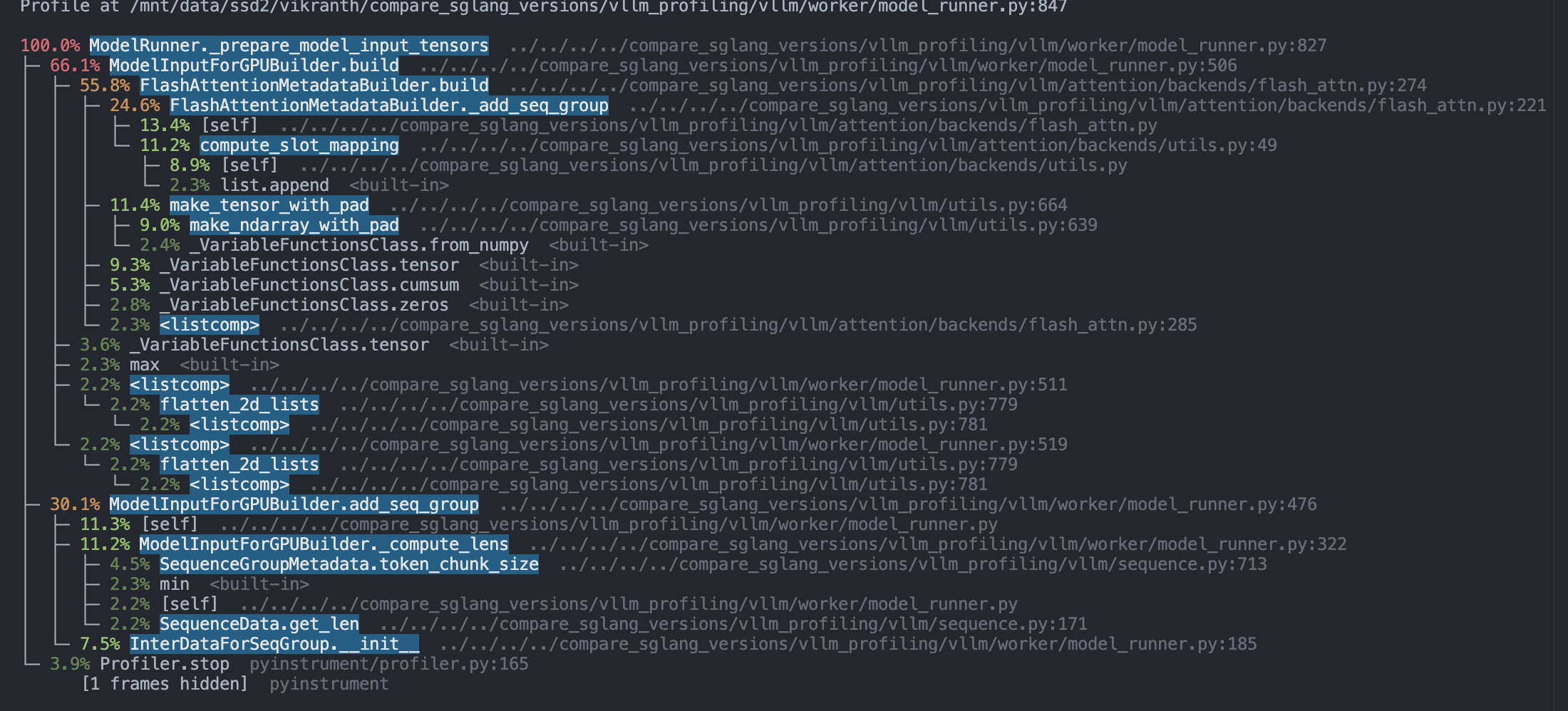

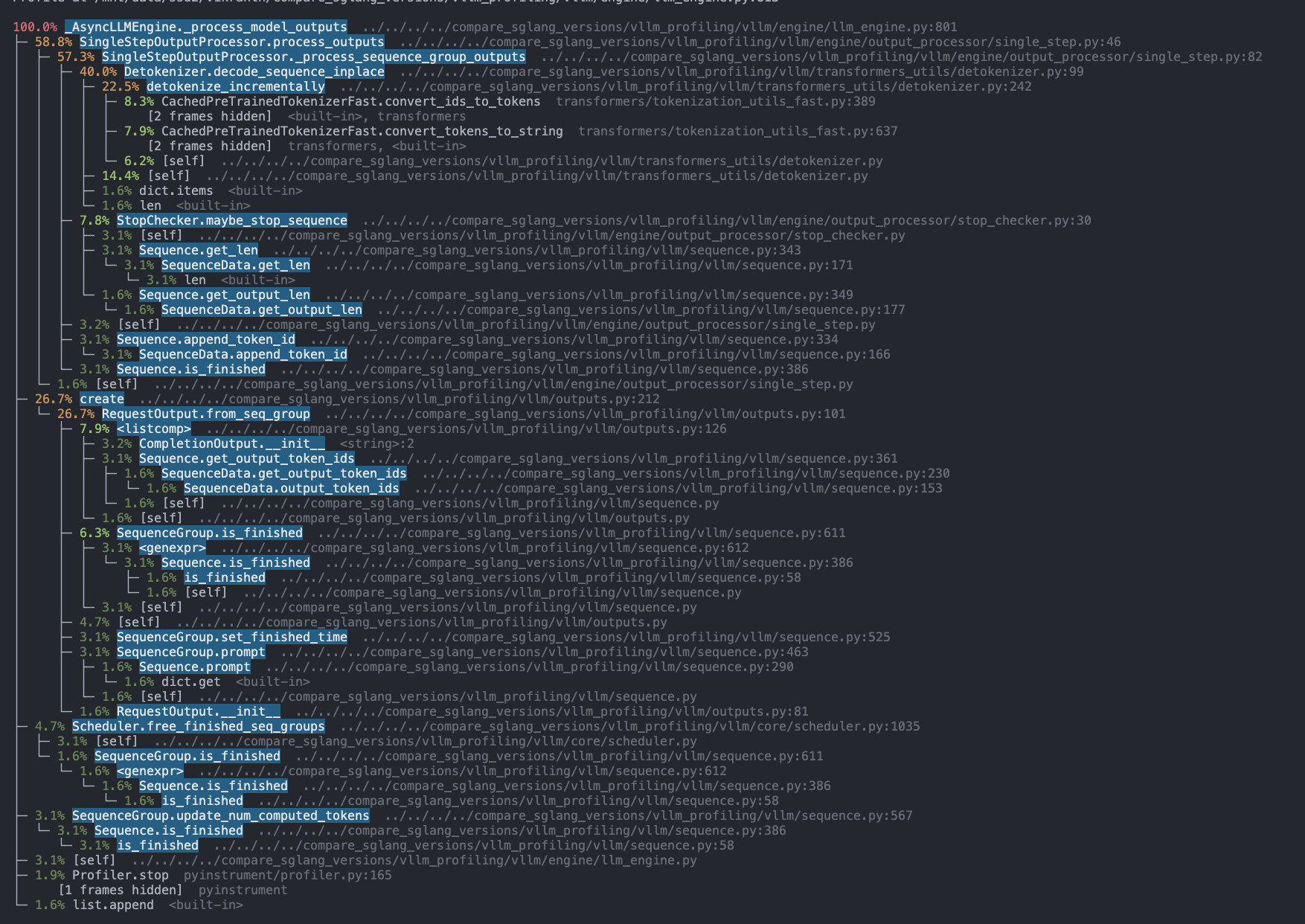

To understand where vLLM’s scheduling overhead comes from, we analyze the breakdown of its scheduling tasks, as shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8 below.

Figure 7: vLLM Scheduling Time Breakdown. Running 1024:1024 with Llama-8B on A6000.

Our inspection of the vLLM code revealed that vLLM has complex Python object manipulation when preparing model input tensors and various metadata, causing the total pre-processing to be large and to increase with more input requests. On the other hand, vLLM detokenize each generated output, causing its post-processing time to also be significant and proportional to the number of output tokens in a batch.

Figure 8: vLLM Scheduling Time Breakdown. Running Loogle with Llama-8B on A6000.

The Loogle workload also incurs non-trivial pre- and post-processing time. However, comparing the two workloads, the Loogle workload incurs smaller overhead in absolute values for model input tensor building and detokenization. Due to the longer prompts and shorter decoding of Loogle, each forward batch contains fewer sequences. Consequently, the input-tensor-building overhead is smaller than the 1024:1024 workload. Meanwhile, fewer requests generate fewer output tokens per batch, resulting in smaller detokenization cost.

Figure 9: vLLM Scheduling Overhead as Per-Iteration Batch Size (in Number of Tokens) Increases

We conducted an ablation study on the number of requests sent to the vLLM serving system. Figure 9 shows that as the total number of requests increases, the relative scheduling overhead also rises. This collaborates earlier analysis of vLLM’s scheduling overhead

Below, we provide a breakdown of the line-by-line trace of running 1024 input 1024 output with LLama- 8b on our local A6000 GPU servers.

SGLang Scheduling Overhead

To further understand LLM inference scheduling time, we examined another serving system, SGLang. We profiled SGLang v0.2.13 and with multi-step scheduling, and chunked prefill budget of 512, with and without prefix caching. SGLang’s multi-step scheduling performs scheduling every K iterations (K=10 by default) when a batch consists only of decoding requests. In our experiments, as new requests keep getting added from the waiting queue, decoding-only batch and thus multi-step scheduling only happens when the waiting queue drains at the end of an experiment. Below, we first present the evaluation results without prefix caching enabled.

Figure 10 SGLang Scheduling vs Forwarding Time on A100 GPUs on Llama 1.3b

Figure 11 SGLang Scheduling vs Forwarding Time on A100 GPUs on Llama 8b

Figure 12 SGLang Scheduling vs Forwarding Time on A100 GPUs on Llama 70b

Figures 10-12 shows the median per-iteration model forwarding and scheduling times for SGLang across various workloads and models. SGLang’s scheduling overhead is smaller than vLLM across different settings, due to its use of vectorized Python operations, its streamlined scheduling processes, and its avoidance of detokenization when users do not provide a stop string. Nevertheless, scheduling accounts for up to 18% of total inference latency in smaller models, as their faster forwarding time makes the scheduling overhead more noticeable.

Figure 13 SGLang Scheduling vs Forwarding Time on A6000 GPUs

Figure 14 SGLang Scheduling vs Forwarding Time on A6000 GPUs

Similar to the vLLM setting, we tested SGLang on our local servers with A6000 Nvidia GPUs and Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 5218 CPUs. In both the A100 and A6000 GPU, the scheduling overhead took a minimal amount of end to end time with at most 5.6%.

Sglang W/Without Radix Cache

Figure 15 SGLang Scheduling Prefix Caching on LooGLE Dataset on A6000

Figure 16 SGLang Scheduling Prefix Caching on LooGLE Dataset on A100

We performed the first set of SGLang experiments without enabling its prefix caching feature to have a setup similar to vLLM. However, by default, SGLang uses prefix caching, a technique to cache and reuse shared prompt prefixes across requests to avoid recomputation. Prefix caching involves maintaining a prefix tree for scheduling and a custom kernel called Radix Attention. To understand the implication of prefix cache, we performed another set of experiments to compare SGLang’s scheduling and model forwarding time with and without prefix caching. Figures 15 and 16 show that per-iteration model forwarding and scheduling times both increase with prefix caching, and the impact is larger with the LooGLE dataset because LooGLE has more shared prefixes across its requests. Relatively, scheduling overhead increases with prefix caching, because the increased scheduling time dominates the increase in model forwarding time.

Conclusion

Our study revealed several interesting new findings about scheduling overhead in SoTA LLM serving systems.

- LLM scheduling overhead can be significant and dominate application end-to-end performance.

- Absolute scheduling overhead grows with both input size and task complexity. For example, vLLM scheduling overhead grows with request counts, while SGLang scheduling overhead increases when enabling prefix cache.

- Relative scheduling overhead is higher when other parts in the end-to-end performance are faster. For example, when model forwarding is faster with a smaller model or faster GPU, scheduling accounts for more relative overhead.

- The more decoding requests there are in a batch, the higher the absolute and relative scheduling overhead. For example, workloads with longer prompts have fewer requests in a batch, resulting in lower scheduling overhead, especially for vLLM. On the other hand, chunked prefill increases scheduling overhead, as it allows a batch to contain more requests and have lower model forwarding time.

- Multi-step scheduling lowers overall scheduling overhead but has its tradeoffs. For example, between two scheduling invocations, no new requests can be added to a batch even if some requests finish early.

- Reducing scheduling overhead may have the tradeoff of increased model forwarding time and vice versa.

Based on these observations, we make several suggestions for future LLM serving system developments. Note that reducing the scheduling overhead is already on the vLLM roadmap.

Co-design scheduling and model forwarding. Our study demonstrated the impact of scheduling overhead on LLM serving performance. As features keep being added, scheduling overheads can no longer be easily ignored. Meanwhile, these added features do often improve the model forwarding performance or overall application capabilities. Thus, the answer to reducing scheduling overhead likely does not lie in eliminating features. We call for future serving systems to measure and optimize scheduling overheads together with model forwarding performance when adding/changing features.

Avoid detokenization when possible. vLLM performs detokenization for all model outputs at every iteration to allow the outputs to be used as text immediately (e.g., comparing output text to a generation stop string). However, such text-based usages of outputs are not always needed. For example, SGLang only performs detokenization if users provide a stop string. Other works also reported serving throughput improvements when removing detokenization. To reduce tokenization overhead when it cannot be avoided, a potential method is to perform detokenization asynchronously while allowing foreground LLM serving to continue with the next iteration.

Improve Python object operations. vLLM’s overhead in building model input tensors and sampling metadata is mainly due to Python object creation and looping. vLLM’s extensive use of dynamic object creation and dispatching can potentially be optimized via PyTorch vectorized operations or native language implementation.

Disclaimer

The findings of this work are based on the authors’ experiments on a limited set of workloads, models, GPU server environments, and LLM serving system versions. This material is based upon work supported by gifts from AWS, Google, and Meta. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of these institutions.